I was not expecting the big reaction my slides elicited when I gave a talk last December at an American Society for Cell Biology conference in Boston. With a subgroup of over a hundred artistic scientists and scientific artists, I shared snapshots along our accelerating march toward a world in which AI can do much of the work of science illustrators—translating complex science into the language of pictures to help scientists explain it. In April 2023 I had tested one of the AI text-to-image models by feeding it carefully written prompts of the kind I might receive from a client. The ensuing laughter from the audience offered a break in the tension of a loaded topic. The result was a jumble of colorful shapes, some resembling DNA. With its garbled letter-like forms, it mostly looked like a botched ransom note. But when I shared a result from the exact same prompt given eight months later—the night before the talk—there was a loud collective gasp. Scientifically it was still non-sensical, but it looked like a magazine cover. How soon before the science catches up?

With the advent of any new tool comes the inevitable hand-wringing about who it threatens to displace. Will science illustrators go the way of the lamp lighter? Or will they be more like the graphic designers threatened by the advent of PowerPoint, unaware that the first website was four years around the corner? I suspect it’s more the latter, and that AI will be just another tool in the scientist’s shed. A band saw does not a carpenter make.

I wasn’t thinking about any of this when I was wrapping up my talk. I was imagining aloud a world in which instead of making art for scientists, we make art with scientists. Sometimes we focus so much on the product that we forget how valuable the process is—its ability to unfold new planes of thought. Designing experiments is an act of creativity, and evidence abounds that success in science correlates with an arts avocation. I fielded a question or two, returned to my seat, and became very excited.

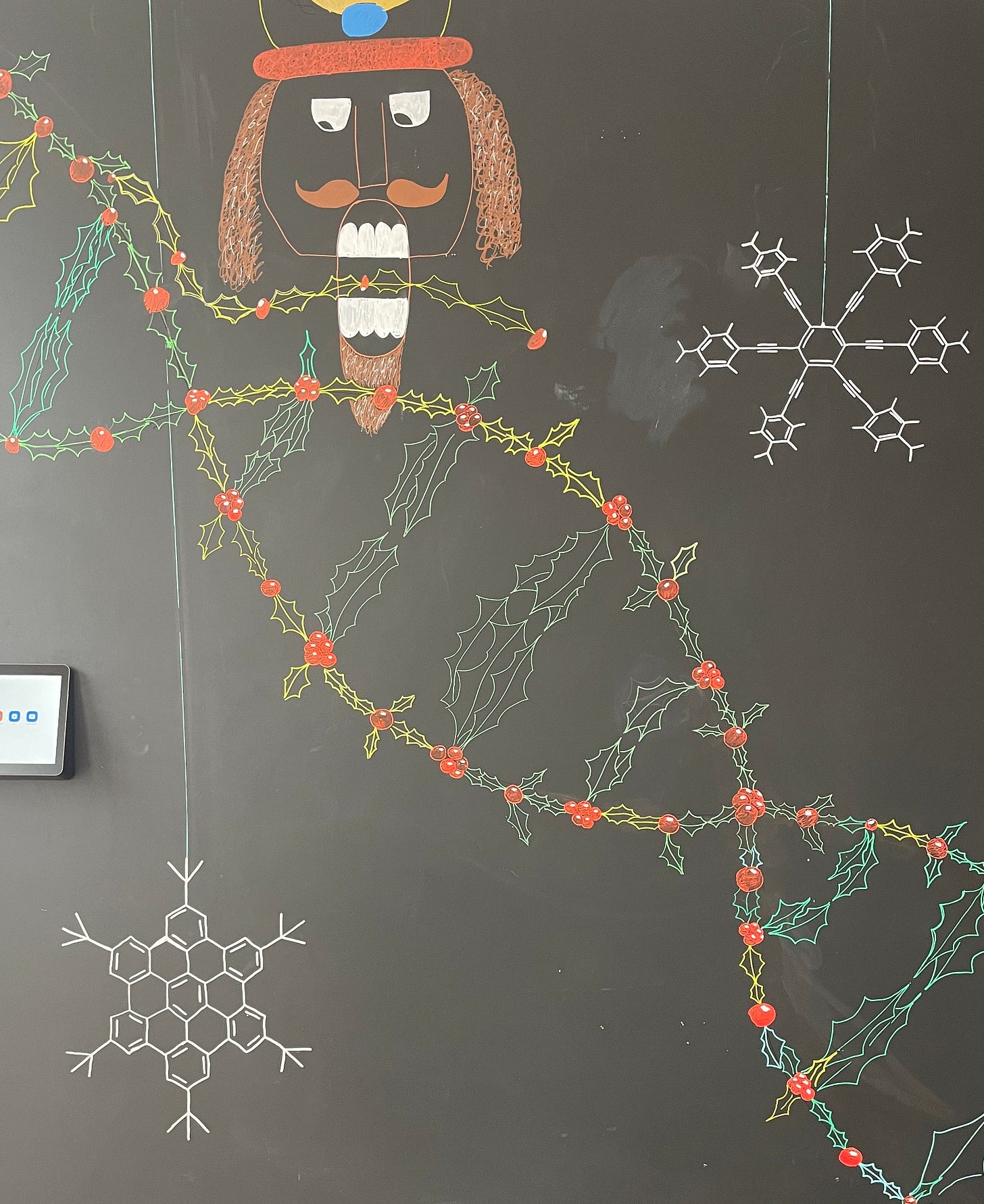

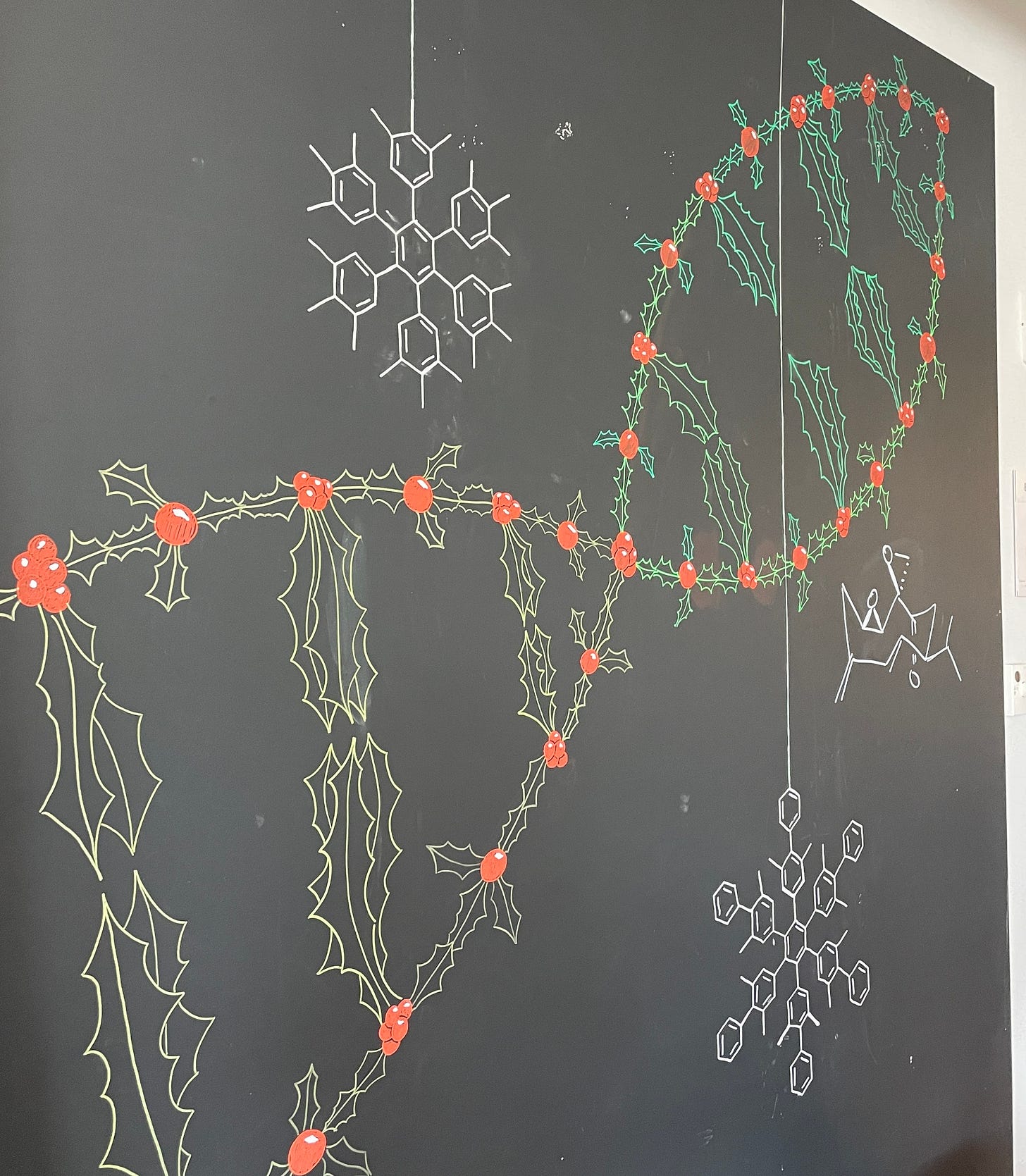

In a serious place like a biomedical research institute, where scientists are working at breakneck speed to cure disease, drawing might seem frivolous. I knew if I broached this in the institute where I work, some scientists would be tentative, even apologetic in their artistic endeavors. Some would dodge my entreaties entirely. A few weeks after my talk at the conference, I was enlisted to decorate a wall-sized chalkboard in the large Cafe for our first-ever work holiday party. Pulled into more pressing projects the day before, I went to bed fretting that I wouldn’t finish it in time. On the morning of the party, as scientists wandered in to get coffee, I asked if they would like to help—no pressure. Soon I had five scientists drawing holly in the shape of DNA and molecular snowflakes with me. One who’d been reticent at first improvised a nutcracker chomping the DNA holly like a famous gene editing tool.

While we drew, we talked. I learned that a young research associate whose jaw-dropping molecular snowflakes were drawing attention had been in an arts and crafts club as an undergraduate at Harvard but now struggled to find his creative outlet. Our founding CEO walked in, took in the scene with delight, and gamely grabbed a stick of chalk to draw a snowflake in the shape of the cockroach pheromone he synthesized in the 1980s.

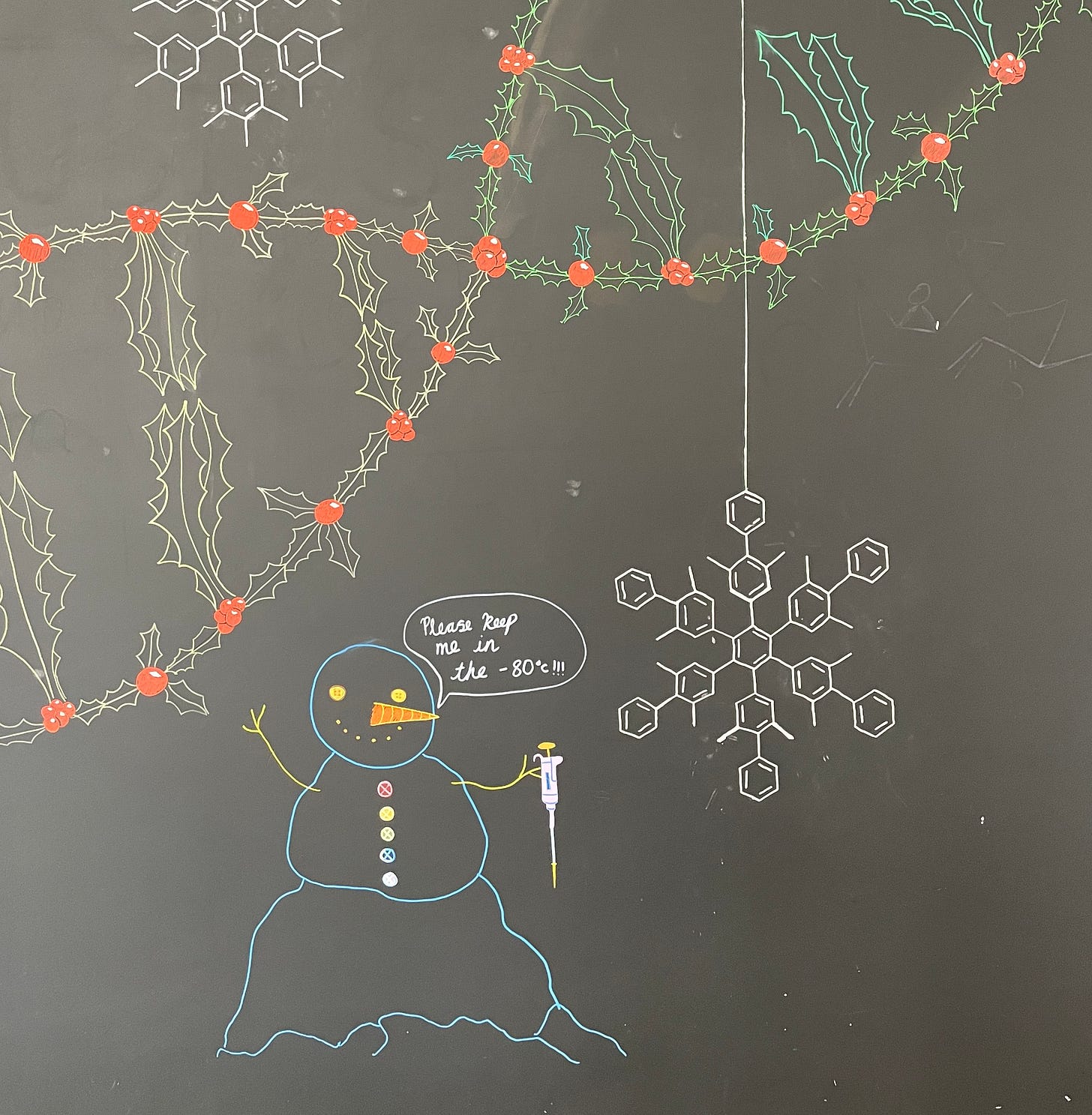

Later during the party, while the rest of us were mingling over signature cocktails to the tune of Fairytale of New York by the Pogues, a research associate sat on the floor drawing a drippy snowman holding a pipette, pleading in a speech bubble to be put into the -80˚C freezer—a staple of biomedical research labs. The drawings we’d made that morning weren’t just decorations. They were permission. Our institute hadn’t even officially launched yet and we were building a culture together.

Encouraged by the chalkboard success, I created a grid on two whiteboards in a narrow hallway on the way to the lab. I gave all employees the vague prompt to claim a box and draw what success in the next quarter looked like to them. I hoped that on every passing they would be re-inspired by what they had drawn from their own hopeful hearts in the thrill of our newness. The young research associates were the first to take up the challenge. The higher-ups proved more challenging. Anticipating an impasse with one particularly reluctant leader, I had an epiphany during a talk when he was probing the esteemed speaker with scientific questions that I didn’t dare ask though they were clanging in my head. When it hit me, my gratitude faded into shame. How could I ask him to leave his comfort zone when I wasn’t willing to leave mine? I shared this revelation with him the next morning while we waited for our coffees to brew. I offered to draw his grid box for him. We brainstormed ideas, and the next day I found that he’d executed our favored one beautifully on the whiteboard. I silently vowed to ask more questions in meetings.

Another scientist with an M.D. and a Ph.D. shyly claimed that he can’t draw. I asked if he might consider borrowing the geometric shapes of Wassily Kandinsky or the childlike encodings of Joan Miro? Who was his favorite artist? Salvador Dali, the Barcelona-trained doctor replied. We nodded knowingly at the difficulty of emulating his style, surreal but paradoxically demanding of realism. Then, helpfully, he offered Jackson Pollack. We laughed about taking the caps off of all the dry-erase markers and throwing them en masse at the whiteboard. It was a perfect metaphor for science—sometimes it’s just throwing things at it and seeing what sticks. He did it!

The novelist Kurt Vonnegut saw the benefit of this long before I did. A biochemistry major in college, he predicted not just AI but also machine learning in his 1952 novel Player Piano. One of his characters—a regular at a watering hole for displaced workers—trained himself to do a lucrative parlor trick in the same way we train models to tell a chihuahua from a blueberry muffin or a fatty liver from a healthy one. But at age 84, in a letter responding to a high school English class, this is what he told them: “[D]o art and do it for the rest of your lives. Draw a funny or nice picture of Ms. Lockwood, and give it to her. Dance home after school, and sing in the shower and on and on. Make a face in your mashed potatoes. Pretend you’re Count Dracula.” He told them not to worry whether they were good or bad or if it made them rich or famous, but rather to do it “to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.”

Will any of this advance science? I don’t know, but I think so. I do know that creativity has always fueled scientific progress, and I don’t think that AI will change that.

Mary, I bookmarked your newsletter to read when I had some time, and I am so glad that I did! I love that you shared your reluctance to step outside of your comfort zone in the talk (been there!) with the more senior leader. First, what an insightful parallel to draw. Second, what a beautiful example of effective communication with a tougher audience member. You used something entirely relatable to connect with him and invited him, again, to collaborate and participate. You convinced him that he, too, belonged in the creative space. Always heartened to know that you're part of the scientific enterprise :)

Great article! All of this resonates strongly with me - all analogous themes at the intersection of computation and science. Will AI replace the computational scientist? Not immediately. Am I using GitHub copilot (a large language model dedicated to writing code)? Emphatically yes! Usually it will auto complete a line of code, sometimes several lines, and occasionally it will teach me a new way of doing things. This is very helpful to me, not that useful to the non-computational scientist. There are tools trying to bridge that gap and I strongly welcome them - I see them as democratizing access to / analysis of large sequencing (and other) datasets.

That's all to say, it's a new tool we (artist, computationalists) need to use and help others adapt to. I think we can all be stronger because of it.