The inspiration for this post began at 5am on a Monday at Boston’s Logan International Airport. I was on my way to Indiana to attend a memorial for a friend—my best friend Shelby’s brother—lost at the unfair age of 50. For some reason my kids like to point out that when someone dies of cancer, the cancer dies too. So, take that, cancer.

My trip there and back was about 30 hours total and included four flights, each so short that the flight attendants took my coffee back while it was still hot. Meanwhile someone at work was waiting for a slide, and I needed, quickly, a silhouette of a human with a subset of specific organs shown. I’d tried to assemble it using handy illustration libraries like BioRender and Servier Medical Art but I wasn’t satisfied with the results. I knew I’d just make it myself, but I was facing the prospect of taking my computer in or out of my overstuffed backpack sixteen times. At the last minute, I’d packed my sketchbook.

The slide recipient was delighted with the hand-drawn anatomy. At the same time, I’d been tasked with coming up with images for a symposium honoring the late Harvard synthetic chemistry giant Yoshito Kishi who died at age 85. So while I was in the air I also drew this, which, by virtue of its physical form, became a gift for his daughter.

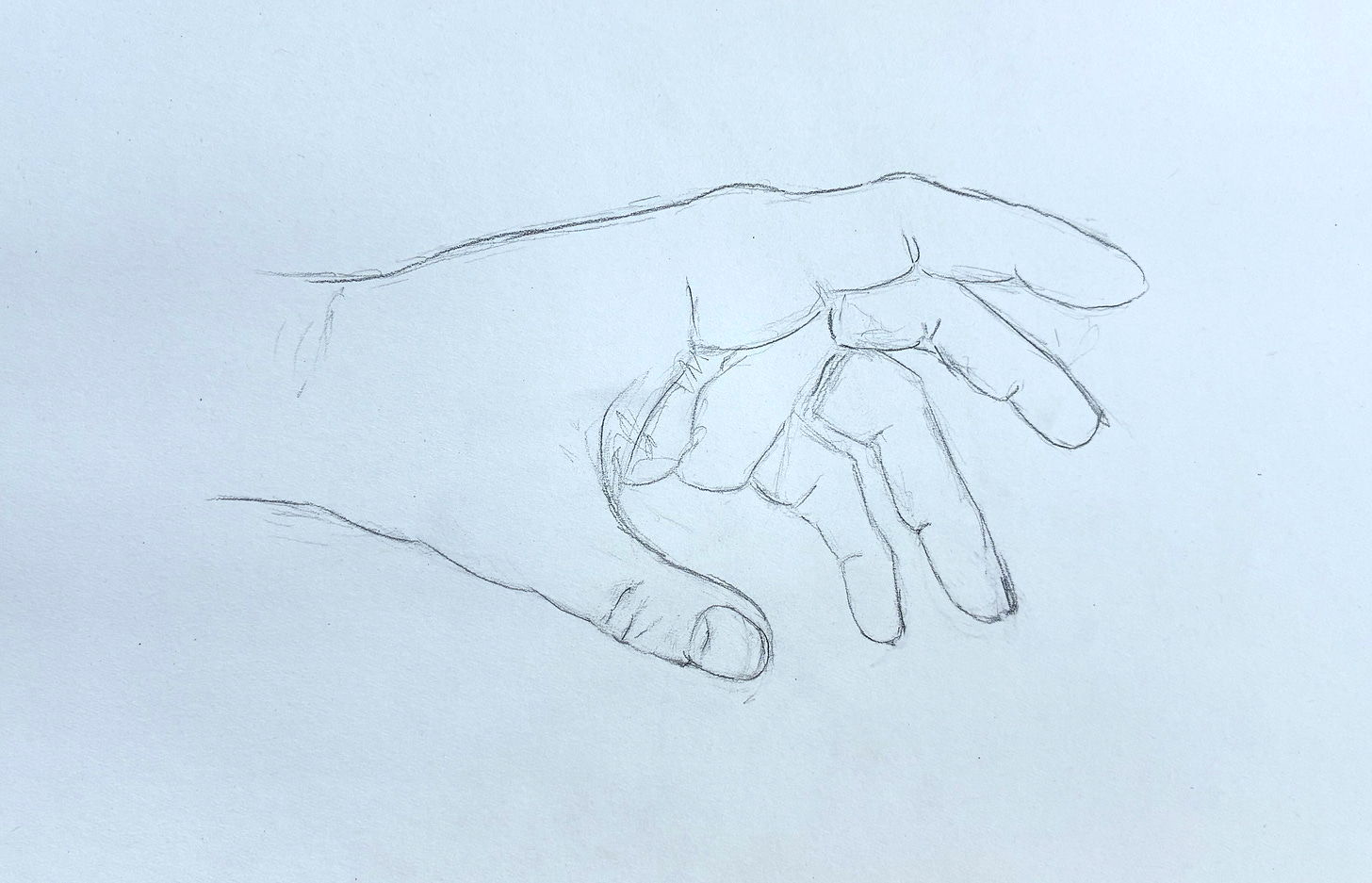

Now I’m back to keeping a sketchbook in my purse at all times like I used to. Not that I’d ever stopped drawing. Early this year when I realized my oldest wasn’t going to have a single art class in all of 7th grade I took matters into my owns hands, literally. Legendary science illustrator Graham Johnson once told me that if I wanted to improve, I should go home and draw my hands and feet fifty times. It’s great advice because these subjects offer constant availability and just the right amount of challenge. (Remember what a hard time AI had with hands for a while?) My son and I stood side by side at a giant sketch pad propped on an easel, our left hands posed in mid-air, as I urged him to see only shapes and lines at certain angles. I told him we didn’t care at all about the outcome, that this was no different than the discipline of his daily workouts for baseball. No winning or losing. We were just getting in reps. The purpose was not to draw, but to see. After the lesson I sought feedback from him because I am needy. He said, “I liked how you told me to not think of them as fingers.”

So what does this have to do with science? If you’re in the business of being in the company of scientists, you’ve probably seen (or been) that person who looks at data and sees what no one else in the room saw. Those people see beyond their expectation of what the data should look like, and that insight can make all the difference. Looking at the world as though you’re trying to draw it can build that same muscle. It might even make us more curious.

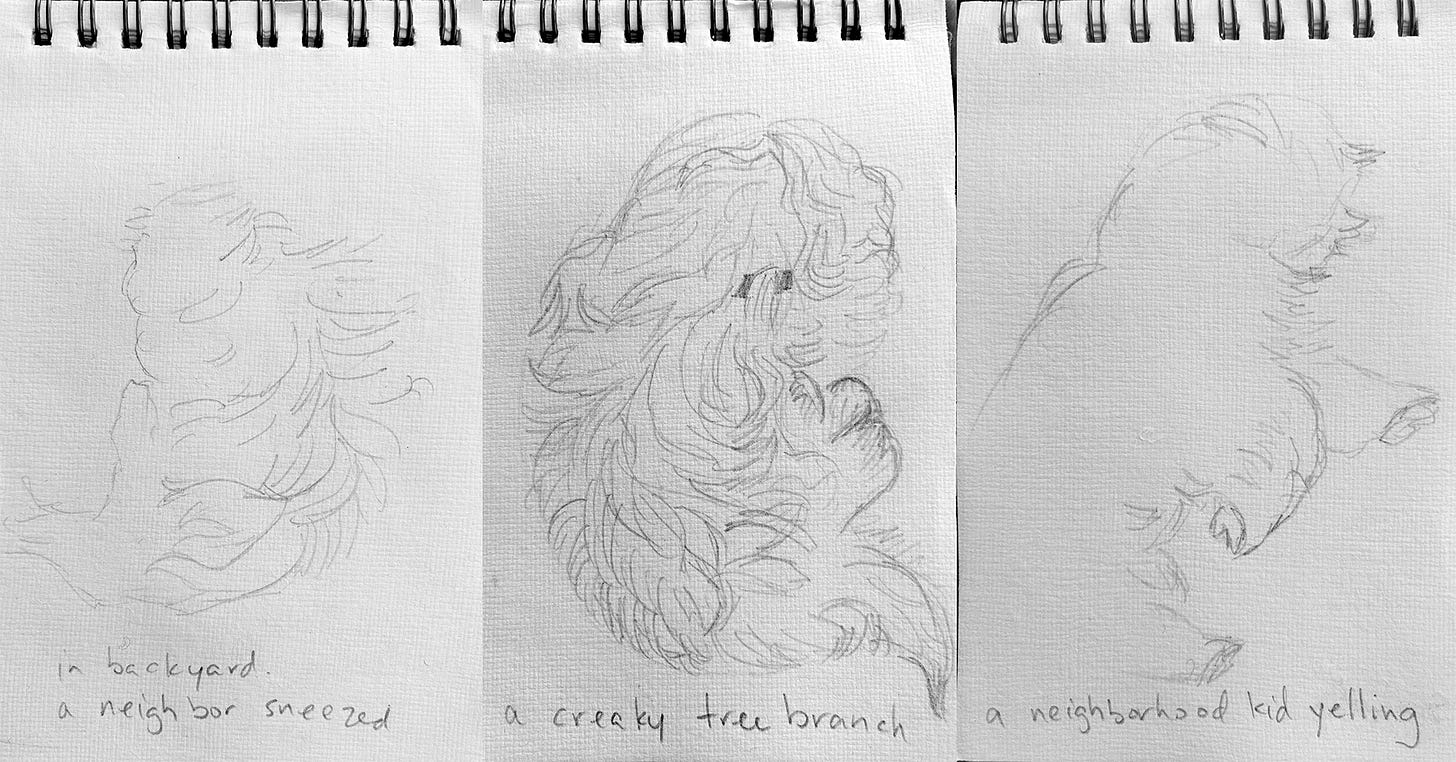

But who has the time to draw regularly? I know, I don’t either. Here is where a technique called gesture drawing is handy. Art students know the technique well as quick sketches completed in 1-5 minutes to capture a pose—the curve of a back, the angle of a head. Lately I’ve been pulling out my sketch book for a few minutes at a time to capture our dog. She is a tiny mop of long black hair from which occasionally appear two eyes and a nose, but more often I’m not sure which end is which. She’s a frequent but restless napper, so unlike traditional gesture drawing, which involves setting a timer, I’m at her mercy. Here are a few sketches done in one sitting, noting the trigger that interrupted each pose.

I might have three seconds or three minutes; there is no way to know. If we reach the time scale of minutes, then there is always an arbitrary moment when I feel I’ve reached bonus time. I can’t believe my luck, because I know that once it’s over, the pose is gone, never to be exactly replicated. It feels like I’ve frozen time or it’s stretched for me the way it slows the closer an “observer” gets to the speed of light. It comes with a heightened state of awareness of all our bygone moments. The feel of your child’s cheek on your bare shoulder. A brother gone too soon. So that I strain even more urgently to really see.

Gesture drawing can be done with anything, including but not limited to a kid watching TV, your own hand, a partner doing the crossword, a pet, a bird out your window, even a complete stranger. I keep a small sketchbook in my purse for the same reason I keep a paperback in there: waiting rooms, airports, long lines, warmups for kids’ sporting events. It’s never too late to start this practice. Richard Feynman started drawing when he was 44 years old and continued for the rest of his life. If you do, please tell me about it! Experience the time warp for yourself. Send me a sketch or two. You can respond directly to this e-mail. If I collect enough, maybe I’ll do a future post about them.